All For The Motherland...And a Bit For Myself (Part II)

The Early 2000s: Russia- Under New Management

“Friend' is sometimes a word devoid of meaning; enemy, never.”

―Victor Hugo

SMOKE clouds choked Moscow's streets on the steamy night of September 9, 1999. When the dust settled, a horrific sight emerged. One hundred-six bodies and body parts lay scattered in an apartment building's smoking ruins. From the large crater visible, first responders quickly identified the disaster as a bombing. A frantic President Boris Yeltsin, just miles away at the Kremlin, immediately ordered a citywide sweep for other threats. Yet, authorities found nothing. However, just four days later, a second Moscow apartment bloc exploded, leaving another 119 dead. Amidst the increasing hysteria, only one public figure appeared resolute: 46-year-old Prime Minister Vladimir Putin.

PUTIN quickly blamed the attacks on terrorists from Russia's unruly and largely Muslim region of Chechnya. The trouble began in 1991 when Chechnya declared independence as the Soviet Union was collapsing. However, the soon-established Russian Federation lacked the stability to crush this separatist movement- at first. Then, in 1994, President Yeltsin finally ordered a massive offensive against the Caucasian-based rebels. Fearful but determined Chechen leaders soon asked volunteers from across the Muslim world for help. Several thousand fighters from Turkey, Afghanistan, and the Arab States immediately answered the distress call. Importantly, recruited jihadists had previous combat experience against the Russians during the recently ended Soviet-Afghan War (1979-1989).

USING this battle-hardened army, the rebels bloodily forced Yeltsin's surrender by 1996. However, victory quickly exposed cracks in the rebel alliance. The Chechen nationalists merely sought independence, like other ex-Soviet republics in the region (Ukraine, Armenia, etc). However, the foreign jihadists dreamed of carving an Islamic state across all of Russia's Muslim-majority regions. Oil money and radical Islamist ideologies from the Arab states fueled this incendiary vision. Politically isolated and impoverished in comparison, the Chechen nationalist could not restrain their upstart allies. Therefore, the foreign fighters unilaterally launched their "Islamic conquest" by invading Chechnya's neighbor, Dagestan, in August 1999. During the Dagestan campaign, militants systemically bombed both Russian security forces and civilians.

THE Dagestan attacks made Putin's explanation for the Moscow bombings appear credulous. Yet, public consensus wavered after a curious incident in the industrial city of Ryazan. On the night of September 22, vigilant citizens spotted two men planting explosives in an apartment building basement. Ryazan police quickly apprehended the shady individuals but, upon investigation, found the suspects were members of Russia's central intelligence agency- the FSB. Embarrassed state officials quickly claimed the incident was a poorly executed anti-terrorism "training event."

MEANWHILE, Putin distracted the skeptical public by calling for an all-out war on the "Chechen Republic." The Prime Minister received firm support from President Yeltsin- still bitter over his own 1996 defeat. Putin began the assault through a systemic air campaign that pulverized most Chechen cities. He then sent 80,000 Russian troops on a slow and methodical advance across the devastated region to crush any remaining resistance. By late December 1999, this calculated strategy successfully trapped the last organized rebel army in their ruined "capital" of Grozny. The public praised Putin for his swift, victorious campaign- especially when compared to Yeltsin's messy 1994-96 war. The young Prime Minister would soon receive a reward for his achievement.

BY late December 1999, Boris Yeltsin was tired of being President. He'd served a messy eight years as Russia's paramount leader marred by corruption scandals, economic crises, and general societal decline. The President also found performing his public duties increasingly difficult due to persistent health issues. Frail and unpopular, Yeltsin resigned from office on New Year's Day 1999. He appointed as his successor Chechnya's conqueror- Vladimir Putin. Now “acting” President Putin reciprocated Yeltsin's generosity by pardoning the retiring leader from any future prosecution.

President Vladimir Putin: Happy to be President…I guess?

DESPITE protecting the widely disliked Yeltsin, Putin remained generally popular due to the "Second Chechen War’s" positive course. This public support was crucial, as the constitution mandated an election within 90 days of Yeltsin's resignation. On February 6, the rebel stronghold of Grozny surrendered after a final grueling urban struggle. This victory pushed Putin over the electoral finish line, and the next month, he was easily elected President of the Russian Federation. Shortly thereafter, in May 2000, he optimistically declared Chechnya fully secured by the Russian Armed Forces.

NOW, the Head of State, President Vladimir Putin, began analyzing Russia’s general situation. He saw few positive national trends except for one: the economy. Two years early in 1998, Russia suffered an apocalyptic financial crisis after Yeltsin's government defaulted on its massive outstanding debts. Amidst the turmoil, the country hastily devalued its currency- the ruble. Fortunately, this risky move stimulated economic growth by making Russian exports more affordable and encouraging the consumption of domestic goods over imports. As the world's (then) 2nd-largest oil exporter, Russia also benefited greatly from an energy price spike begun in 1999. These positive developments meant that Putin inherited a favorable economic situation characterized by trade surpluses and a booming oil industry.

THE political landscape appeared less optimistic for the new President. In the summer of 2000, the Russian Federation was a messy political entente divided into 89 "federal subjects." These subjects were known as krais, republics, or oblasts, depending on the region. Under Yeltsin's leadership, the subjects were allowed maximum autonomy. Unfortunately, this "grace" turned into contempt for the federal government. At best, this subject defiance manifested as underpaying state revenues or ignoring federal directives. At worst, federal weakness provoked full-scale rebellion and separatist movements like in Chechnya.

IN May 2000, Putin addressed this bureaucratic insolence by grouping the federal subjects into seven large federal districts. He then appointed "Presidential Envoys" from amongst his trusted advisors to govern the newly created subdivisions. This move instantly put the unruly federal subjects firmly under Presidential power. Although the move had no constitutional basis, Putin's consolidation of power received strong support from federal politicians. Contrastingly, subject governors watched impotently as their autonomy dissolved virtually overnight.

THE other significant political challenge Putin faced involved confronting Russia's ultra-powerful business elites, known as the oligarchs. These men had become fabulously wealthy during the business-friendly Yeltsin years by acquiring massive stakes in key sectors, including finance, energy, and telecommunications. In return for this "permissive" corporate environment, oligarch money fueled Yeltsin's 1996 re-election campaign and second administration.

YET, upon assuming office, it became clear that Putin had no intention of being the oligarch's puppet, as his predecessor had. The first skirmish occurred over Gazprom, a formerly state-owned energy corporation that Yeltsin's administration largely privatized. Despite being Russia's largest company, asset stripping and embezzlement by oligarchs on the Gazprom board caused underperformance. Sensing an opportunity, Putin leveraged the Russian government's still substantial Gazprom stake to purge its board and replace them with Presidential loyalists. For outsiders, this move looked like Putin using government power to break up a corrupt cabal. However, the President soon used Gazprom's massive profits as his private piggy bank.

THEN, instead of confronting the powerful oligarchs collectively, Putin carefully targeted the most prominent among them. The President first took down Vladimir Gusinsky, who owned Russia's most popular television network- NTV. Gusinsky had been an early Putin critic, and his network even openly questioned FSB involvement in the 1999 apartment bombings. Therefore, just days after Putin assumed office in May 2000, the FSB raided NTV's Moscow offices. The following month, Russian prosecutors arrested Gusinsky on alleged financial crimes. Although soon released, a frightened Gusinsky sold most of his NTV assets and quickly fled abroad. Shortly thereafter, the newly Kremlin-dominated Gazprom acquired a majority stake in NTV. Putin's administration now controlled Russia's largest energy company and TV network.

Vladimir Gusinsky: “Getting out while the getting is good”

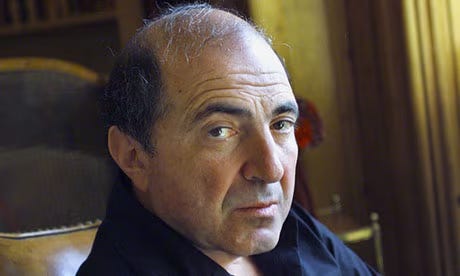

YET, this was only the start. The President next destroyed the most powerful oligarch: Boris Berezovsky. A former Soviet engineer, Berezovsky had become a telecommunications magnate by purchasing Russia's former state-owned TV network, Channel One. Berezovsky then used the platform's profits and influence to become Russia's political "kingmaker." Indeed, the TV tycoon was Putin's largest donor in the 2000 Presidential election. Seeking more direct power, Berezovsky successfully ran for a seat in Russia's legislature- the Duma.

NOW holding legal authority, the tycoon turned on the young President he had sponsored. Berezovsky first clashed with Putin over the federal subjects "reforms". However, the new President's successful power struggle with Gusinsky was the final straw. Instead of direct confrontation, Berezovsky patiently waited for an exploitable scandal. This opportunity arose in August 2000 when the Russian submarine Kursk exploded during a military exercise- killing 118 sailors. The incident was personally damaging for Putin since the public judged him as unsympathetic towards the many grieving families. Berezovsky soon utilized Channel One's reach to broadcast this criticism of Putin nationwide. Yet, the President wasted no time hitting back. Similar to Gusinsky, Berezovsky was quickly slapped with trumped-up financial crime charges and forced abroad. The Kremlin then gobbled up Channel One's assets- making it a state-controlled TV network once more.

Boris Berezovsky: (Former) Top Dog

YET, Putin had little time to celebrate after a shocking world event weeks later: 9/11. Appalled, the Russian leader was the first foreign dignitary to call a shaken U.S. President George W. Bush. Indeed, Putin and Bush had formed a strong mutual respect following a productive bilateral meeting in June 2001. This relationship largely hinged on the belief that Russia and the United States shared a common enemy in Islamist terrorism. Indeed, both the al-Qaeda network that planned 9/11 and many Chechen jihadists had links to extremist training camps in Afghanistan. Therefore, Putin strongly supported the initial American invasion of Afghanistan that toppled al-Qaeda's Taliban backers in late 2001. Then, as the Afghanistan mission shifted to "nation building," the Russian President provided America with key logistical support through several bases in Central Asia.

DURING the years following 9/11, Russia itself suffered several brutal, terrorist attacks. The most notable occurred on October 23, 2002, when Chechen militants stormed a theatre in Central Moscow and took over 900 hostages. After a multi-day standoff, Russian security forces funneled sleeping gas into the cramped building before clumsily storming it. Between overdoses caused by the gas and fatalities in the vicious close-quarters shootout- 132 hostages died during the incident. Chechen terrorists hit Moscow twice more in the following year. During July 2003, suicide bombers attacked a music festival and killed 15 concertgoers. Then, in December 2003, another bombing took six innocent lives right outside the Kremlin's gates in Red Square. Similar attacks occurred across the country from 2002 to 2003. A particularly shocking one happened in the Caucasian spa town of Yessentuki, where Chechen bombs destroyed a train- killing 41 vacationers.

THESE incidents viscerally indicated that Putin's "Second Chechen War," supposedly concluded in May 2000, had morphed into a more terrifying conflict. After Russian forces seized the Chechen "capital" of Grozny following a vicious siege, the surviving rebels scattered around the countryside. Once hidden among Chechnya's rugged mountains and pine forests, the insurgents re-adopted their successful 1990s strategy by launching persistent guerilla attacks against Russian troops. Starting in 2001, mainly at the radical jihadis' behest, the Chechen rebels attempted to demoralize Russian citizens through the previously described suicide bombing campaign.

HOWEVER, some Chechen fighters became increasingly disgusted with both the Islamist jihadis' radicalism and the civilian death toll in suicide attacks. Many of these conflicted individuals soon changed sides. An early turncoat was Akhmad Kadyrov, a leading religious figure (mufti) and respected veteran of the First Chechen War (1994-96). Kadyrov's preeminent stature enticed so many rebel defections that he formed a pro-Russian militia known as the Kadyrovites. The Kadyrovites proved highly effective at assisting federal security forces with intelligence gathering, policing, and counter-guerilla operations. Putin quickly rewarded Kadyrov's efficacy by making the ex-rebel Chechnya's new "ruler."

Akhmad Kadyrov, early 2000s: Putin’s “Top Guy” in Chechnya

WHILE the Kadyrov relationship bloomed, cooperation with Putin's other counter-terrorism partner, U.S. President Bush, withered. The first breach occurred in 2002 when, driven by Post-9/11 hysteria, President Bush abruptly withdrew the United States from the Cold War-era Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. Yet, the event that enraged Putin most was America's invasion of Iraq in March 2003. On a ground level, Russia's extensive business activity with the Iraqi government evaporated after the U.S. assault. Yet, more importantly for Putin, the Iraq invasion indicated that the Bush Administration was not merely concerned with "killing terrorists" but regime change in the name of "spreading democracy." In Putin's cynical view, this outlook meant that Bush would overthrow any state challenging U.S. hegemony to install leaders friendly towards American interests. The Russian leader also strongly criticized how America attacked Iraq without approval from the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). For Putin, it now seemed that there were no legal or institutional limits on American military adventurism.

AMIDST this tense atmosphere, another explosive event occurred in November 2003. Georgia, a former Soviet republic bordering the Russian Caucasus, was suddenly rocked by mass demonstrations against long-term President Eduard Shevardnadze. Although sparked by allegations of election rigging, the nationwide anger stemmed from years of corruption and economic mismanagement under the Georgian President. After a three-week standoff, frustrated opposition protestors stormed the parliament as it opened the session. Fearing imminent violence, Shevardnadze promptly resigned.

Georgia’s Rose Revolution, 2003: Well, that escalated quickly?

ALTHOUGH many in the United States and Europe celebrated Georgia's "Rose Revolution" as a triumph for democracy, Putin saw things differently. While Shevardnadze had been generally pro-Western, the Georgian leader had also resisted intense American pressure for economic and political reforms. Therefore, Putin asserted that the demonstrations were not spontaneous but organized and funded by the U.S. government to remove the independent-minded Shevardnadze. The Russian President cited the fact that several Georgian opposition leaders received financial backing from American non-governmental organizations (NGOs) as evidence of "foreign interference." The dark paranoia that America was willing and able to topple regimes on Russia's doorstep permanently altered Putin's relationship with the United States.

THE Russian President was particularly concerned that Western governments would undermine his rule through the oligarchs. These business elites often worked, traveled, and lived abroad. Therefore, oligarchs forged deep personal, professional, and even political connections in countries such as the United States or the United Kingdom. No oligarch worried Putin more in this regard than Mikhail Khodorkovsky. In 2003, Khodorkovsky was the country's richest man through his ownership of Yukos, an energy company that produced 1/5th of Russia's oil. Yet, the energy baron was also a strong critic of Putin, with many powerful friends in the West, including former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. Khodorkovsky even founded an NGO called Open Russia that (with generous Western donations) lobbied for anti-corruption reforms in Russia's government and business sector.

KHODORKOVSKY believed his personal friendships and high esteem with Western elites would save him from the fate of other defiant oligarchs. This assumption proved incorrect. Shortly after the Yukos CEO directly lectured Putin on corruption during a televised meeting, he was arrested and charged with (per the playbook) several financial "crimes." Yet, unlike previous oligarchs, he was not allowed exile. Instead, Russian prosecutors swiftly convicted Khodorkovsky and hauled him to a Siberian prison. Yukos' high-value assets were then gradually absorbed by the Kremlin.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky on Trial, 2003: He’s seen better days

THIS severe example permanently crushed oligarch resistance. Individually or in groups, the business magnates began cutting deals with Putin's government. The final terms agreed on were simple: the oligarchs could retain their businesses and fortunes, provided they never criticized Putin or his administration. Putin also extorted most oligarchs into personally paying him an indefinite "fee" for avoiding any future "issues" with the Russian government.

IN addition to imprisoning oligarchs, the Russian President also created some new ones. These emerging "Putin-circle" tycoons generally came from three sources:

Childhood buddies or family friends from Putin's youth in St. Petersburg (then called Leningrad)

Veterans of the intelligence services, especially the KGB in which Putin served from 1975-1991

Former colleagues from the St. Petersburg city administration where Putin worked during the early-mid 1990s.

REGARDLESS of their origins, these new oligarchs mainly concentrated in the energy, defense, and financial sectors. Within these industries, their Presidential connections resulted in preferential accounts, contracts, clients, and regulations. Other Putin cronies chose to work directly for the Russian state. The President assigned these trusted allies to leadership positions in sensitive security departments, including the FSB, Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD), and Special State Police (OMON). Russians called this security clique who underpinned Putin's growing rule siloviki or "people of force."

THE siloviki felt their new positions were secure after Vladimir Putin handily won re-election as Russia's President in March 2004. In fairness, it wasn't much of a contest. By 2004, the Kremlin effectively controlled all major television networks. Therefore, state media made it impossible for rival candidates to broadcast their platforms nationally. Despite this election interference, Putin enjoyed genuine popular support as his first term ended. The economy was humming from rising oil prices and better business practices encouraged by the government. Crime, poverty, and unemployment were all down compared to Yeltsin's unfortunate tenue. Surprisingly, the even Chechen bombings were generating a "wartime" patriotic feeling among the people. Average citizens also praised Putin for confronting the hated oligarchs associated with the national dysfunction of the 1990s.

DESPITE these adulations, the Russian President wasn't satisfied. Still simmering from Georgia's "Rose Revolution" and the Iraq War, Putin began quietly planning to strike back at the West.

Continued in Part 3…